Until it’s gone syndrome: seeing home through the eyes of distance

From a forgotten Mediterranean hillside to the streets of Paris and Barcelona. On presentism, memory, and the clarity that comes from leaving.

I recently came across an old picture taken near our country home in Southern Europe over a hundred years ago, and it profoundly moved me.

The picture also showed me the deception of presentism: we think the world is what we see today, and the reality in front of us appears as unfathomable as if it had sprouted by spontaneous generation, but what we see around us is an outcome affected by a series of actions that others took long ago. You see a forest and think it’s been there forever; only it grew when people abandoned the fields surrounding a reservoir built in 1928.

What I see today from the rocky hill where the hamlet and the house stand today is a water reservoir below going around a meander covered by the trees and shrubs of a typical Mediterranean forest, and behind it, the soft forested mountains that separate the sea from the wine-country valley of Penedès one hour down the coast from Barcelona.

Today, the dry, limestone-rich area houses a natural park cataloged as a biosphere reserve of Mediterranean flora and fauna. Still, a mere three generations ago, the surrounding agrarian society was cultivating even these marginal, stone-covered lands between the interior valley and the other side of the slope facing the sea (the Garraf Massif).

Landscapes are hard to truly “see”

And that’s what I saw in the picture: no reservoir, but a small river that sometimes dries out in summer, with edible gardens on each side and bare hills where local farmers grew wine, as they still do in less hilly areas of the historical small region within Catalonia. The picture also highlights old trails for animals and people connecting the old mill on one side of the hamlet to the irrigated garden area on the other side, as well as the cultivation of vines in the dry, stony, and higher areas.

The memory of the area’s current inhabitants has long forgotten that, not long ago, the current protected forest didn’t exist, and the “natural” area was part of the local farms, which grew wine and, to a lesser extent, olive trees, carob trees, and cereals that best withstood the area’s dry conditions like local varieties of wheat, barley, and rye.

Life was hard at the margins of the region’s economic centers in pre-industrial times, as evidenced by the coastal local fisheries and olive groves around Vilanova i la Geltrú, as well as the fertile Penedès Valley. Until the twentieth century, life in the rocky area between the coast and the valley was harsher, and estates were more challenged by years of drought.

Over the centuries, people built their own houses using local soft stone and natural mortar, adding later materials that required more efficient kilns, such as brick. The arable land was dry, poor, and littered with stone formations that prevented agriculture altogether. However, locals took advantage of the abundant calcareous rock to produce limestone for construction, which they used locally and exported across the region.

Like a rolling (lime)stone

Today, the small lime kilns they used (“forns de calç” in Catalan), sunken, round constructions made of stone with a small opening at their base to light and feed the fire and a top opening where limestone was loaded, are still visible between the trees and shrubs now covering the hillsides. Along with agriculture, kilns were the reason why big forests had vanished from the area, for the kilns used wood and charcoal to reach the needed 900–1,000°C (1,650–1,800°F) maintained for days at a time to reach the desired chemical reaction: calcination (in which limestone turns into quicklime, releasing carbon dioxide as a byproduct).

After firing, the kiln was left to cool on its own, and a few days later, the quicklime (“calç viva” in Catalan) was extracted for direct use in mortar, whitewash, and soil treatments. Nowadays, the techniques that locals used to build and finish their houses, from hydrated lime to whitewash and lime plaster, are making a comeback due to their aesthetic appeal and seamless blend with the vernacular, as well as their lack of toxicity.

But these ways and the landscape they created are long gone from the place and the memory of locals, many of whom descend from those keeping the vines, trees, and kilns now buried by the forests. In this case, forest regeneration took hold, but such substitution, which occurred during the uneven transition from medieval times to modernity, has produced many realities that are less appealing than a healthy forest.

Today, those interested in ruined lime kilns can find many remains in the forests of Garraf and Penedès. They appear as stone-ring structures, partially sunken or embedded in slopes, often overgrown. Many of them are cataloged by local hiking groups and historical associations and appear on GIS layers used by hikers.

In a way, these people fight against presentism, telling the trained eye that the “pristine forest” facing them is a construct as modern as any other in a place that was already heavily transformed during Roman times over 2,000 years ago (Tarraco, current-day Tarragona, 40 minutes away down the coast, was the capital and main city of a big chunk of Northern Spain, the Roman province of Hispania Tarraconensis).

Constructing a longer “now”

Presentism causes us to forget how things were and how they can be. It also produces the so-called “until it’s gone syndrome.” We become so used to what we have and perceive the world from the standpoint of our senses. Due to hedonic adaptation, we become so accustomed to what we have that we fail to notice transformations until they reach a tipping point and occur.

When we visit relatives we haven’t seen in a while, we perceive changes in them more drastically, but we often are polite and don’t tell them how things have changed; what we fail to understand is that this shock goes both ways, and they experience the same when looking at us and, especially, to our children, which can go from little kid to an adult in the making in a short period.

We often view reality from a particular place and mindset, making things so gradual that we lose track of time’s footprint, no matter how we call it: entropy, aging, erosion, decay, impermanence, transience, etc. failing to fully value or appreciate the things we have: good health, a supportive family, certain resources, the physical ability to accomplish many things in a single day, etc. It’s only when we lose such things that we really cherish what we had, a curse as old as humanity.

How can we have the “taken-for-granted” mindset? Do we need to experience upheaval, illness, or loss to appreciate what we have? How can we better understand that our surroundings are often a byproduct of choices made by us and others (now and in the past), and therefore we have the ability to shape our interior and our surroundings? These questions regarding impermanence have affected thinkers and poets, from Michel de Montaigne to Ralph Waldo Emerson, who have explored the cultivation of gardens of the mind and spirit, as well as the physical ones: orchards, groves, enclosures, parterres, yards, humble patches, or small-scale Arcadias and Edens.

Learning to appreciate things before they’re gone

We don’t deeply question reality for the sake of our sanity. Still, every Philosophy 101 class should start with the fact that our shortsightedness is by design (that is, for survival) in reality perception or the fact that we see the world through the narrow window of the present tense, which keeps moving its mark so the now is soon a more and more vague before, while what’s to come next seems to underdeliver (also by design).

This fact has influenced the way we see the world and given way to all sorts of biases, including presentism, or the fact that we see things from our “now” and so we tend to extrapolate present-day ideas into depictions and guesses of the past (and future).

Since we live in the present tense, we fall into many psychological traps. One of them thinks that all things past were better, and entire industries (and now, also political careers) are fueled by nostalgia and retrospective idealization, often employed with bad faith.

There are also more positive aspects associated with the “Until it’s gone” syndrome: often, people leave their country or birthplace, either by choice or due to forced circumstances. When leaving one’s homeland, a particular, intellectually fruitful clarity emerges. Much like we fail to appreciate the people around us, our comforts, our health, or our freedoms until they’re disrupted or lost, we rarely grasp the full meaning of a culture and a place—especially when we grew up there—until we leave it.

It doesn’t surprise me each time that I read that this or that thinker, writer, impresario, etc., only learned to reflect on their place of origin once they had left it.

Why?

When we grow up in a place and culture, we’re inside the nuances of its grammar: smells, social codes, silences, injustices, comforts; these things may feel “normal,” yet they are also idiosyncratic and represent a shared “reality distortion field” (say, certain regions of Europe enjoying bullfighting, eating frogs and rabbit, etc., versus other places considering it an oddity). These particularities, whether geographical or temporal, affect the way we interpret reality and the way we think or write about the world.

In this sense, exile (voluntary or not) becomes a lens, converting the “taken-for-granted” into the “newly visible.”

Meeting all kinds of people—and oneself

During his first stay in Paris, James Baldwin realized that once American writers had left their country and gathered in Europe, they could see each other with sincerity and solidarity, regardless of their race, gender, or sexual orientation.

What Baldwin most appreciated about those years (1948-1957) was the unjudgmental anonymity he found, as well as the Parisians’ reserve and indifference towards him. By knowing no French and being unable to communicate or claim a spot in French society, he explained that he had spoken or done little during his first year abroad other than keeping his senses open to observe and listen to the world around him. And, to Baldwin, this indifference and respect for his self-imposed alienation was a blessing, for the writer and intellectual was fighting to emerge back then.

“In Europe, I met all kinds of people. I even met myself.”

Europe wasn’t simply an artistic refuge but also some sort of free zone where deeply ingrained prejudices lost their meaning, and the weight of social hierarchies and racial identity had little value: Baldwin repeated in interviews, conceded to the French radio and literary journals, that his fellow American friends confronted their constructed national illusions rather brutally when abroad: at home, people of European descent had only one universal way to agglutinate around common values, consisting of recognizing their antagonism towards others (mainly black people), whereas in Europe, there was no such construct of whiteness, for people from different regions and countries differed culturally and linguistically.

Given this observed reality, American writers—regardless of their background—encountered a kind of liberation. For some, self-exile was an escape from Puritanism or conventional careers, and for others, from homophobia or racism. Europe offered them a chance to begin again and construct themselves beyond American categories.

Writing from a vantage point

Like the Lost Generation before him, who had lived in Paris after the Great War and written (sometimes lucidly) about American culture from a distance, Baldwin profited from the geographical and intellectual distance to reflect on the barriers he’d encountered during his life.

From afar, it was easier for him to describe the fate of a black family in 1930s Harlem. He followed suit, exploring his sexual identity, the contradictions of African-American religion (which would emerge during the Civil Rights era), and the search for identity when one didn’t fit into the socially accepted categories of the bountiful America of post-WWII expansion and opportunity, from the GI Bill (signed in 1944) to the FHA (Federal Housing Administration loans), to the extended post-New Deal protections.

Like many others who traveled to discover who they truly were, James Baldwin’s experience in Paris prepared him for a return to the US. In The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American, Baldwin wrote:

“Europe has something we have not yet achieved: a sense of the mysterious and of life’s inexorable limits—in short, a sense of tragedy. What we have, and what Europe most lacks, is a new awareness of the possibilities life can offer. In the effort to merge the vision of the Old World and that of the New, it is the writer—not the statesman—who plays the central role. Though we may not yet be fully convinced, the inner life is a real life, and man’s intangible dreams have a tangible impact on the world.”

A very particular elevator

I think about all this as I text with my oldest daughter, who is now traveling in Europe with her senior year high school friends now that they finished the year and know where they’ll go for college, leaving behind the comfort of their teenhood and “traveling abroad,” becoming adults and growing their own agency in the process.

They chose my city (and the town where our children were born), Barcelona, from the many places where they could have begun their trip. In messages with Kirsten, our daughter explained how the “grammar” of the culture represented by Barcelona came rushing to her as she walked through places: smells, social codes, accents, and many other little things that she wouldn’t put into words even if she could. She’s forgotten many things but still feels at home, even if she has an “accent” when speaking to locals.

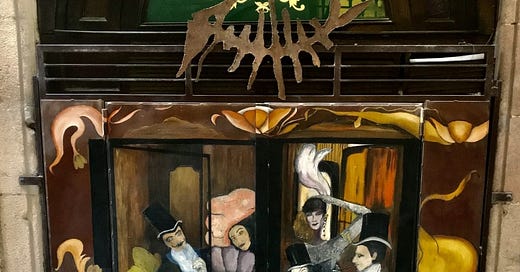

Before she started her trip, we talked a bit places to visit, and I mentioned as an oddity/curiosity that her aunt (my sister, that is) worked many years when she was at college as the manager of a small, quaint bar in the Gothic Quarter called L’Ascensor, where you have to go through an old art deco/modernista elevator to finish inside the dark and small bar, a place for aspirational bohemians that used to drive locals when I was young.

I had forgotten about this tip until I got a few pictures today and my daughter and friends were sitting at the place, using the same chairs and tables that my sister used to arrange every night the place was open, which I visited sometimes, alone or with friends.

I’m not sure why I thought about Paris and Baldwin when I saw them; perhaps because I also learned to know who I was when I went to live in Paris during the annoying times when there was only one topic of discussion in Barcelona, and I felt we needed some space to breathe. Or rather, to go somewhere else for a while so we could get some perspective on our own lives.

Senior trip musings

But the tale is, of course, more complex, for our daughter feels more at home in Barcelona, Paris, or the Bay Area (our current home) than we parents probably do.

Perhaps, once she is in college, our daughter will reflect on her sense of belonging and continue to make her own way.

We don’t just lose places to time—we lose our vantage point on them. And yet, it’s in that loss, or in stepping away, that we finally begin to see.

Perhaps that’s why watching my daughter walk the streets of my own past stirred something so complex: not just nostalgia but recognition. Recognition that what we love often lies dormant in the background, like those buried lime kilns under Mediterranean brush, until someone stumbles upon it again with new eyes.

Her visit to that tiny bar reminded me of Baldwin’s quiet year in Paris (watching, absorbing, preparing to speak but only when he was ready). Sometimes, we need to disappear from a place to truly learn how to talk about it. Sometimes, our children return to it before we do.

We spend our lives immersed in layers of impermanence—of landscapes transformed, of beliefs revised, of childhoods turned into someone else’s stories—and yet we often need distance to understand that the ordinary was never ordinary at all. The smell of the local bar. The pattern of dry stone terraces. The feeling of home that survives accent, language, or time.

From a lucid poet buried in exile

We live in the present, yes—but to live meaningfully, we must learn to see through it. To imagine the trails once walked, the people who built with lime and hope, the quiet revolutions of forest and family. To remember what shaped us—before it’s gone, or before we are.

And maybe that’s the gift of the “until it’s gone syndrome.” It reminds us that clarity can come not only from loss, but from attention. From stepping back far enough to see that we were part of something vast, textured, and worthy of care. From letting go long enough to return, not just wiser, but more whole.

“Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino y nada más;

Caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace el camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino

sino estelas en la mar.”Traveler, your footprints

are the only road, nothing else.

Traveler, there is no road;

you make your own path as you walk.

As you walk, you make your own road,

and when you look back

you see the path

you will never travel again.

Traveler, there is no road;

only a ship’s wake on the sea.Caminante, no hay camino, Antonio Machado (from Provervios y cantares, 1912)

Last August, we lived for a month in Mexico. I don't know Spanish, and my broadest memory of time there is that of trying to find how to act again when we returned home to Boston. I feel that I deferred the "learning about myself" to the return home when I would see which of the ideas I had, and which of plans regarding what to do to enjoy life more, stuck when they were thrown at the wall. I don't know why life felt so the same in Mexico but my plans felt only real and enactable where I came from. Even the trip there, the plane ride, felt like a simulation: you're home and then you're away in a matter of hours. It is amazing how little significance life can have when our experiences are convenient.