Slouching Towards the Singularity: AI musings from Telegraph Avenue

On Telegraph Avenue from Oakland to Berkeley, where rebellion once thrived, conformity and resignation now scroll by. What does it mean to stay human in a world written by prompts?

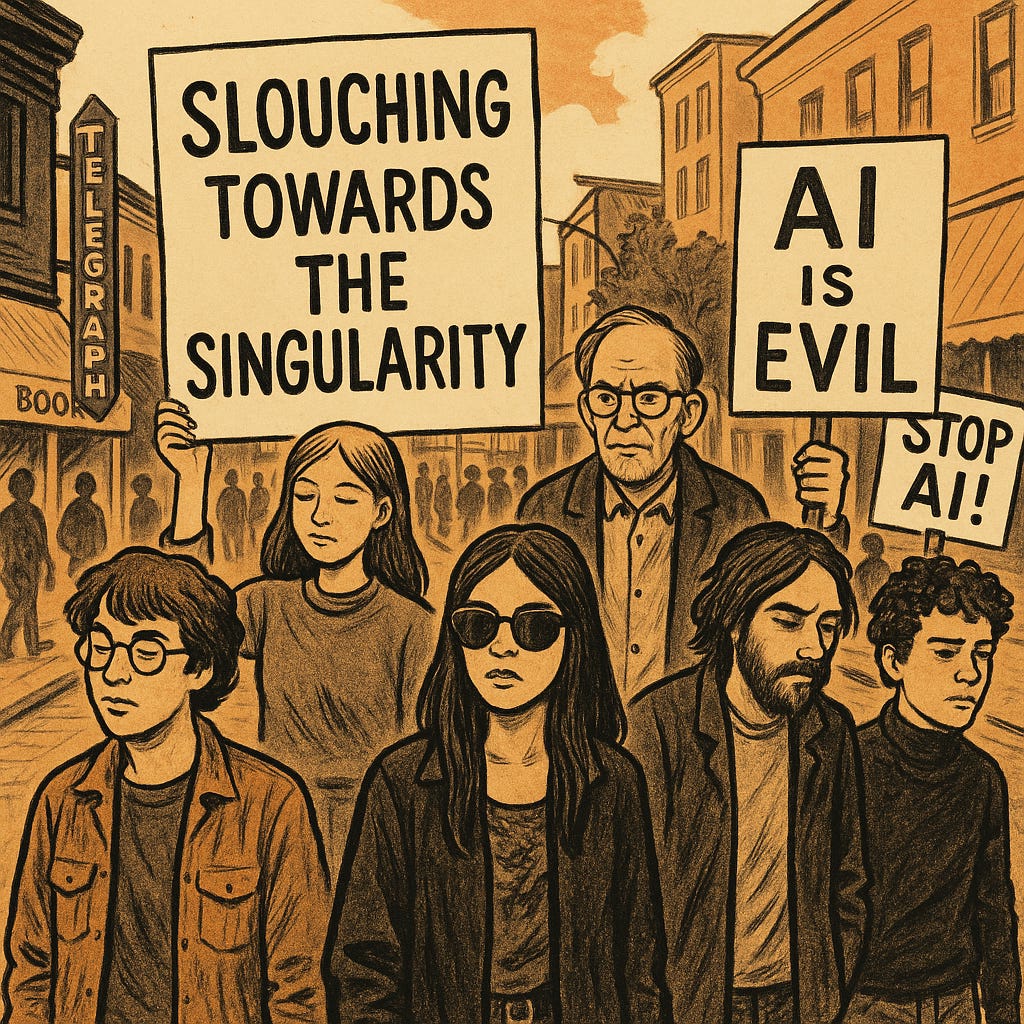

If Joan Didion were to start this article, she could have drawn our attention with something like this: “The future arrived on Telegraph Avenue not with a bang, but as a notification.” Because these days, even protests against technological lobotomization are powered by QR codes.

AI encapsulates the impossible promise of technological solutionism. Tired of writing or thinking on your own? Prompt a chatbot. Need a last-minute memo for the consulting presentation that allows you to charge as much as you want for what’s essentially assuring others that their work matters? Prompt a chatbot.

Regardless of the field, the AI workaround is now pervasive, from government and corporate advisers to high school students. Yet, every day, AI users are also dealing with the consequences of accepting good-enough-but-not-great platitudes as “the right response” to complex questions that often lack a straightforward or unequivocal response.

The effect of the human extensions we build

Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan saw it coming long before most of us were born: the belief that every real-world problem can be solved with the right technological fix. Decades ago, he warned of a future shaped by pervasive media—tools that wouldn’t just extend our capabilities, but reshape how we think, feel, and relate to the world.

Over the decades, in tandem with the internet, personal computers and smartphones have begun to deliver on the promise of solutionism, albeit not quite living up to it. That said, coming short in many matters didn’t prevent the companies that capitalized on the emerging digital world from becoming the biggest and most powerful entities ever created. Nvidia, the provider of the sophisticated chips required by AI models, recently became the first company to reach a $4 trillion valuation (which, if it were a country, would make it the sixth-largest country by GDP). Not bad for the small company making chips for gamers that I wrote about in niche articles after college, when I joined a Barcelona tech publishing company (back when techies would buy magazines to spot some trends of an emerging world).

AI has captured the public’s imagination and value in less than a decade (OpenAI was founded in December 2015). Now, AI seems to offer a new perspective on McLuhan’s concerns about our incremental dreams regarding technology. When Steve Jobs stated that personal computers were a bicycle for the mind, he merely recognized the process: “media” and “technology” are extensions of human functions, complementing our potential. If the wheel enhances our feet, the phone extends our voice, and TV extends our eyes, digital media extends the reach of our central nervous system. It seemed that personal technologies would make meliorism inevitable.

The Faustian bargain was inevitable, and in retrospect, AI is the outcome of the mentality initiated by technological solutionism. But, McLuhan says, we should be wary of the consequences of such a bargain, because any incremental enhancement takes a bit more of personal agency and autonomy from us:

“Every extension of man, especially technological extensions, has the effect of amputating or modifying some other part of him.”

It’s not about how much we give up of our own agency for the sake of alleged progress and convenience, but how much personal freedom we give up with a smile, let alone putting up a fight.

What AI means for the college experience

With the digital world, many have come to realize that there can be too much of a good thing, and our reliance on smartphones can reach unhealthy levels; as it often happens, many of the early adopters and trendsetters who were at the vanguard of adopting smartphone apps for everything are now advocating for the other extreme, sharing in social media (this isn’t a world to dig too much into people’s contradictions) the newly exclusive promises of the analog world: film cameras, handwritten letters, well-kept notebooks, music in vinyl and other promises of less dependent, mode analog and tactile experiences in a world that’s being saturated by AI prompts (and unauthentic, unfathomable entertainment).

However, this lucidity won’t prevent us from feeling privately excited and using AI tools for as many things as we can, hoping that our AI prompts will be unmatched and that, somehow, we’ll untap all the advantages of using LLMs that we don’t control, and our mastery will differentiate us from the rest.

In other words, if everyone—whether people disclose it or not—is already using AI for many things and expects to extend its use to as many realms in life as they can, how will people differentiate their AI-enhanced work and life actions from the similar platitudes churned by everyone else? Will AI detector checkers (powered, of course, by AI) kickstart the digital witch hunt of the future?

When I ask this question to my teenage children, they don’t see any conflict of interest and don’t think their humanness or uniqueness is at risk at all. Our oldest daughter was born in 2007, the same year the first iPhone was released, whereas our youngest was born in 2012, a year of breakthroughs in deep learning and image recognition.

At the same time, as our oldest daughter is about to start college with the intention of majoring in English in arguably the best place available to do so, UC Berkeley, this conversation will have an extensive follow-up, for AI is already transforming her field and many others: if college students use AI for everything (writing, designing, coding, brainstorming, researching, or forming ideas), how is their formative experience going to be impacted?

And, above all, how to remain unique, authentic, “human,” if we lose confidence in traditional hard-work methods to think and develop work capable of making us distinguishable and hard to replace (either by others or, more likely, automation)?

In a sea of platitudes, human imperfection can shine

The commercial applications of AI are being integrated vertically in every possible human field, and AI is currently the buzzword that every service and company needs to repeat or risk being sidelined, regardless of its power. Apple, the big-tech company most reticent to invest heavily in its own AI tools, hasn’t convinced investors that Apple Intelligence is anything but an intention to partner with others to offer non-critical AI integration in its devices, which partly explains why its value has stalled over the last year. If Apple can’t escape the hype surrounding AI, let’s consider our position as mere individuals poised to feel the consequences of its pervasiveness.

Once AI is pervasive, the tool’s value and usefulness will be taken for granted and devalued. Social media is already saturated with AI-generated content, the same way that the playlists recommended by Spotify to its growing user base are increasingly low-cost creations aided by AI, which cost no royalty fees to the company, increasing benefits; similarly, other content platforms such as Netflix and YouTube will be impacted by low-end content mainly generated by automation.

In this context, if we were to advise people who are about to start college or are just entering their first jobs after graduation, telling them that AI has no value or should be avoided at all costs would likely tank their professional prospects. Back to Marshall McLuhan, technological determinism isn’t a given, and each of us will use AI differently. As extensions of ourselves, digital tools will shape us, but we still have a say: effects and outcomes will depend on how we use the new pervasive tools.

Perhaps, as the AI watershed moment approaches, the best-adapted individuals could recognize the potential of authenticity in a world whose reality is increasingly mediated by large language models. In this context, non-AI quality interactions would be perceived as a luxury, with human work (not efficient, imperfect, quirky, with a clear soul) as some kind of new, irreplaceable artisanal good. “Human-made” could become the new “organic” (for example, a good writer describing the world from a unique perspective can earn a steady following, the same way people in the sixties appreciated Bob Dylan’s lyrics amid a more banal pop industry).

Just the beginning: after smartphones

Similarly, AI overuse could rely on remixing already existing content and experiences, with depth and original (and first-person) quality accounts of events and places becoming increasingly rare. As a result, people demonstrating lived experience and original thought could emerge above a sea of mediocre takes. Lived experiences will remain attached to relationships and places, turning the localism of “being in the world” into a truly human differentiator.

AI can’t replace excellence or quirkiness, but can help us with menial tasks, allowing us to free time to spend more time exploring, spending time with others, reading, wandering, etc. For example, it may help us gain some context about a place we’re getting to know by generating fine-tuned responses to specific questions.

Suppose I’m walking along Telegraph Avenue in the East Bay. I can imagine the place through the lens of others (Jack London growing up in Oakland and imagining his alter-ego character Martin Eden—whom we imagine taking a tram down the street—, Jack Kerouac’s The Subterraneans, Joan Didion when she attended Berkeley, etc.). I can also lack any of these references, and asking AI about such real and fictional experiences by writers and artists may provide us with a glimpse that opens like a portal to a richer dimension of reality.

Hence, we can use AI more as an enhancement and less as a substitute. That said, AI may make our current state-of-the-art personal devices obsolete very soon with voice-activated AI wearables like the ones ex-Apple Jony Ive’s new startup will be designing for its new owners, OpenAI. Maybe, the devices of the future will take even more agency from us, suggesting to us what to see somewhere and how to see it.

Luddite signs in Telegraph Avenue

If I’m walking down Telegraph Avenue, instead of referencing Jack London or Joan Didion, we might end up with a quick summary of what to do from a very utilitarian, commercial point of view. In this situation, we’d be passive subjects being monitored and driven by AI. We wouldn’t have the upper hand anymore, and those controlling the LLMs would have in their hands the biggest tool of mass manipulation ever built.

Perhaps, the smartphones of today will look like semi-innocent windows to digital content compared to the passive-aggressive smart devices of the future, which promise to replace our critical thinking with personalized models that will put Samantha, the assistant from Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), in the dust.

One decade after the release of Theodore Twombly’s (Joaquin Phoenix) improbable love story with an LLM, everything aspires to be AI-powered, and many people are developing deep emotional attachments with chatbots. No wonder our attitudes towards the AI-powered stage of digitalization vary, depending on one’s level of alienation: from resignation to cynicism, to a belligerent Luddite reaction.

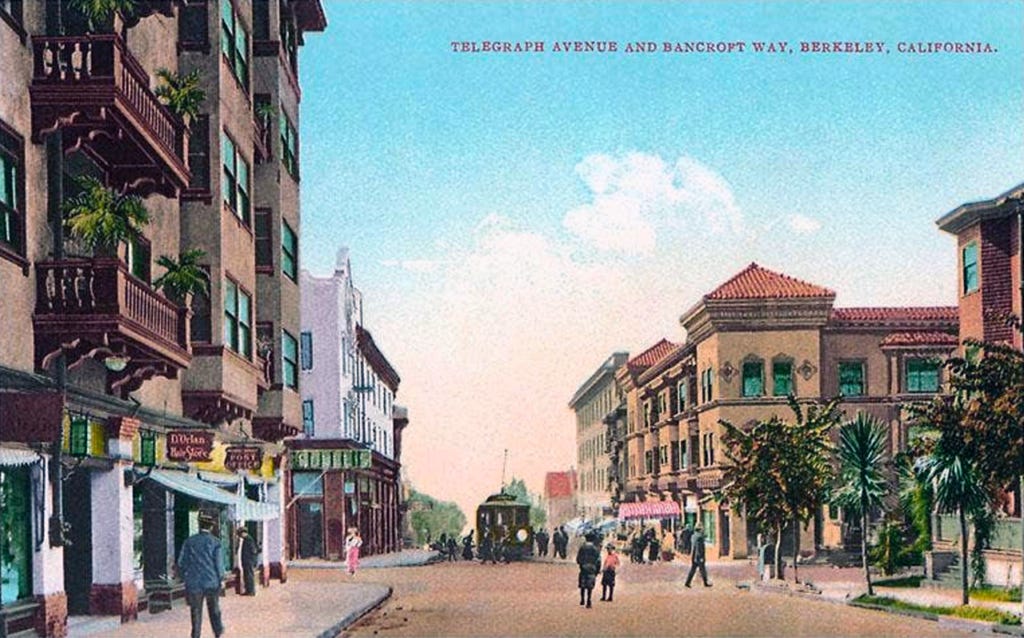

Just before writing this, as I was crossing the historic Telegraph Avenue (a way less lively artery cutting across the San Francisco East Bay between downtown Oakland and Berkeley’s Campanile than one hundred years ago) near Willard Middle School and saw that somebody had glued a poster to the light pole adjacent to the sidewalk, with two capitalized words in white over a red background simply read: STOP AI. Below, in smaller letters, the reason: “Protest & Presentation,” with day and location, as well as a QR for each of the two events, and a URL.

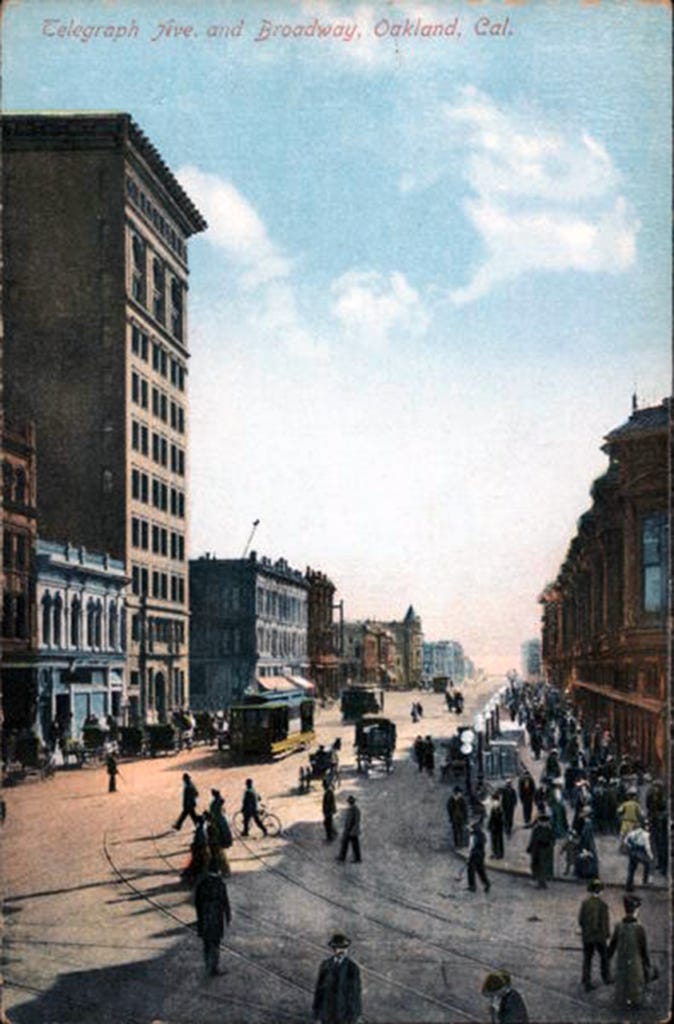

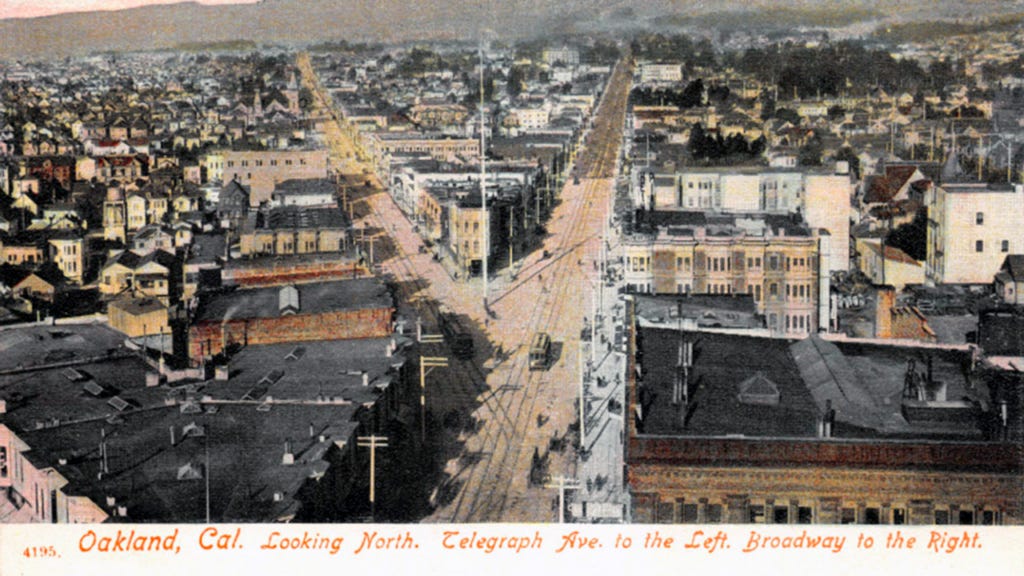

I realized it was somewhat ironic to find such a sign at a street that got its name from the mid-nineteenth century ultimate innovation, the telegraph: in 1859, the Alta California Telegraph Company, a company owned by the state which preceded the Transcontinental Telegraph (which, along with the railway, would transform North America forever), laid out a line between Oakland and Martinez along the Peralta estate in Temescal.

Better misfits than automata

That way, the previous pathways through Temescal and the Claremont between Oakland and Berkeley got a new, wider dirt road that connected Oakland and the private College of California, predecessor of the University of California (the first UC). Its trustees laid out a subdivision south of their campus to finance the university.

Soon, the parts of the new avenue closest to Oakland’s downtown on one side and to the university on the north end became lively, buzzing areas served by horsecars from 1869, replaced later on by a steam dummy line, and decades later by an electric streetcar line. The connection stimulated the entire area, attracting businesses that served the new neighborhoods. Some of these, such as the upscale Claremont subdivision between the two towns, became desirable districts in the hills for those seeking more space and cleaner air.

Today, like in its beginnings, the vibrant lode around Telegraph revolves only near Oakland’s downtown and in the opposite extreme, the five-block stretch just south of the University from Bancroft Way to Parker Street that during decades attracted an amalgam of visitors hanging around cafés and restaurants, bookstores, record stores and second hand clothing shops, the scenery where college students, hippies, artists, eccentrics, and all sorts of transient people collided.

There, figures of the counterculture and literary characters drifted from San Francisco to the North Beach scene, and sporadically to the East Bay around Telegraph Avenue as a spillover of the bohemian/intellectual in search of gatherings: the late-fifties beatniks featured in Jack Kerouac’s The Subterraneans (like the character of Mardou Fox, based in Alene Lee, visiting friends near the avenue), and also as the background of cafés, bookstores, and demonstrations of the sixties that Joan Didion (who attended Berkeley after being rejected by Stanford), Tom Wolfe, and others chronicled.

Young Joan Didion walking down Telegraph Avenue

Today, the first-person style of Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem (the collection describing her experiences in California during the 1960s), analytical and ironic, would struggle to make sense of the place as she did in the sixties, although for very different reasons.

She would see how the rebellion of yesteryear was today’s merchandised conformism. Didion, a genius at detecting the emotional tension beneath surface events, would struggle in an age of ambient dissociation, in which people perform ideology more than trying to make sense of it. She would also notice the paradox of a powerful, well-funded university that costs like an Ivy League for out-of-state students towering beside sidewalks and parks where people struggling with mental illness and addiction live in tents.

Didion would also notice the change in the overall campus culture; today’s bright and itchy students are less interested in Chomsky than startups, DAOs, machine learning, and chatbots, whereas the Avenue where Free Speech was once shouted now monetizes conformity and one only true connection: that of alienated individuals with their respective smartphones.

Some of the bookstores are still there, but most passers-by are more interested in signaling how such places from the past (like Amoeba Records) relate to the reality they filter through their phones. Perhaps, Didion would realize that the most subversive types are trying to escape the algorithm, trying to rediscover the meaning of living—or is it “analog living”?

The price of human autonomy

Perhaps that’s the true irony of this moment: the most powerful tools for communication in human history are taking shape before our eyes, only to find ourselves more unsure of what’s worth saying—and who is really saying it.

Time goes on Telegraph Avenue as anywhere else; the street changed so quickly that soon the promise of the telegraph got left behind, a relic of the past in an area set to build the technology that would deeply transform the world. The telegraph once promised connection; now the signals we receive are ghostwritten by something trained on everyone and belonging to no one.

In this reality, analog doesn’t mean obsolete—it might just mean authentic, sometimes a matter of posing. But, as we enter the new era, a mere conversation without transcripts feels more and more refreshing, almost a rebel action. So does writing in a notebook, or forgetting the smartphone, to realize one can live without it, just alright.

Perhaps, not that far in the future, a walk with no wearable may just be the first act of a human rebellion. In the age of AI, maybe the most radical act will simply consist of being oneself, there, unscripted.