Echoes across the water: the San Francisco Bay islands

From Dumas’ Château d’If (Marseilles) to Alcatraz and Angel Island in the Bay Area, islands have long mirrored society’s fears, fantasies, and the eternal return of events.

Picture the merchant sailor-turned-Romantic hero Edmond Dantès, the soon-to-be Count of Monte Cristo, being sent at the beginning to the worst imaginable punishment in 19th-century France: the dreaded Château d’If —an island fortress that faced the harbor of Marseilles like a bad dream—from which no prisoner had ever escaped. Or the tiny island of Montecristo, just out of the Tuscan archipelago, where Dantès claims Father Faria's treasure and builds his lair.

Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo was a blockbuster in its time, captivating 19th-century readers through the feuilleton (serial) format in newspapers from 1844 to 1846. Each installment ended with suspense, making readers eager for the next issue, just like a modern-day video streaming binge. It also turned settings like the Château d’If island-fortress into instant legends, just like movies about escaping Alcatraz would do the same about the island prison facing San Francisco in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Built in the 16th century to defend Marseilles from sea incursions, the Château d’If later served as the insular prison where the most dangerous felons and political prisoners were sent, never to come back. I recently watched and enjoyed the most recent cinematic adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo (2024), a French big-budget production starring Pierre Niney as Dantès/Monte Cristo.

Island-fortresses and the collective unconscious

There is no question that such an evolution and idea of a tiny island with a purpose could be extrapolated to Alcatraz. Both garrisons and prisons faced a city that served both as a quarantine environment and a cautionary tale for those outside, just like a panopticon embedded in people’s minds, so there’s a constant presence of the modalities of social control in front of the city streets.

Of the many islands that populate the San Francisco Bay, one has captured the imagination of the collective unconscious. Nicknamed “The Rock,” for decades, it meant total isolation and harsh punishment to locals, a visual warning of what could happen to anyone who decided to cross any line.

Alcatraz reflected a punitive philosophy of old-school justice at the westernmost limit of a country that had finally completed its expansion across a continent. Bringing it back as a prison for migrants is the ultimate provocation to many, some sort of return to a place of exclusion that everybody can see, the antagonist of another symbolic Bay Area islet, Angel Island, also known as the Ellis Island of the West.

Located near the upscale community of Tiburon near Sausalito, Angel Island was the main immigration processing center of the West Coast from 1910 to 1940, welcoming immigrants from Asia. Asian immigrants weren’t treated lightly.

After exclusionary laws against non-Europeans from the late 19th century onwards, immigrants were often detained for weeks, months, or even years on the island. Like Alcatraz, Angel Island is now a state park that includes the remnants of the immigration facility: visitors can walk through the rooms where immigrants were held, including bunk rooms and interrogation areas.

Old poems carved on the wall

Many detainees at Angel Island used classical Chinese verse to write poems of sorrow, homesickness, and hope, following tonal and rhyme patterns. Most of them are carved into the wooden walls of the detention barracks. In a piece for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Joy Lanzendorfer called them The Talking Walls of Angel Island, which opens with one of them:

In the last month of summer, I arrived in America on ship.

After crossing the ocean, the ship docked and I waited to go on shore.

Because of the records, the innocent was imprisoned in a wooden building […]

Sitting here, uselessly delayed for long years and months,

I am like a pigeon in a cage.

There are many more:

In the quiet of night, I heard, faintly, the whistling of wind.

[…] The floating clouds, the fog, darken the sky.

The moon shines faintly as the insects chirp.

Grief and bitterness entwined are heaven sent.

The sad person sits alone, leaning by a window.

When the Trump Administration announced it was considering reopening Alcatraz, many representatives and people in California and the Bay Area asked: why and how?

The symbolic enclave, which can be seen from many downslope streets in San Francisco as well as Sausalito on the north shore of the Bay’s opening, closed 60 years ago, to the relief of technicians at the Bureau of Prisons, who complained about its decay, inefficiencies, and obsolescence at a time when maximum security prisons were built inland.

A place in living memory

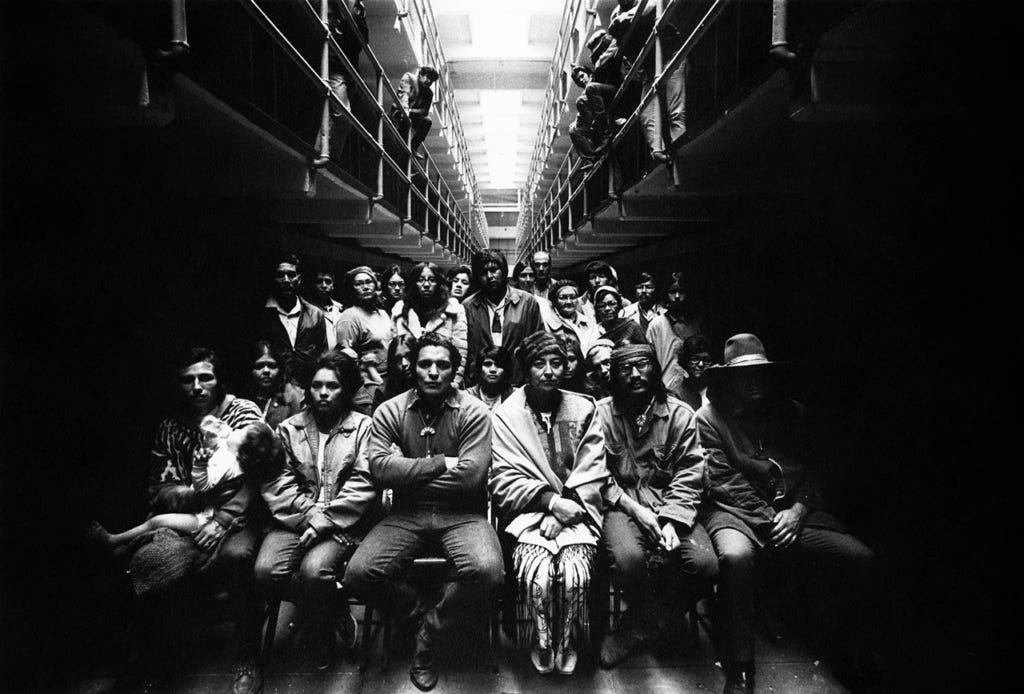

Alcatraz later became a symbol of political resistance associated with Native American activists. In 1964, only a year after the prison’s closure, a small group of Lakota Sioux tried to organize a protest to attract the media (a tactic not that different from Trump’s provocative proposals): They mentioned the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie (which had allowed the return of unused, marginal federal land to Native ownership).

Richard Oakes was the face of the so-called Red Power movement. Shortly after the 1969-71 occupation of Alcatraz, he was fatally shot near Annapolis, in rural Sonoma County north of San Francisco. He was 30 years old and was unarmed when shot by a local, who called him a “troublemaker.” In 2023, Jason Fagone and Julie Johnson wrote a piece on the San Francisco Chronicle about Oakes’ killing; it's worth reading.

It was a brief protest, but activists took notice, and five years later, the so-called Indian Occupation of Alcatraz (1969-1971) was mainly led by Bay Area college students of Native American heritage, although not exclusively. The activists invoked again the Fort Laramie Treaty, gathering attention and getting the support of a sizeable part of the Bay’s counterculture, along with celebrities like Jane Fonda and Marlon Brando.

Alcatraz may be an archaic concept to hold dangerous inmates (most notably Al Capone), then a utopia to revert land to the area’s wiped-out and assimilated natives, though the idea persists with the stickiness of a Jungian archetype. To even float the idea of reopening Alcatraz to house migrants while they’re on their way to deportation was quickly dismissed as outlandish and also made these buried memories emerge back to the surface. They’re still there.

Francis Drake and his antagonists

However, it rang a bell across the Bay Area, reminding people that San Francisco isn’t a city but an idealistic archipelago at the end of the world. Scattered through a bay blessed by its natural beauty and all-year-round pleasant weather, small islands were mapped and used by European explorers, from Spanish expeditions to Sir Francis Drake’s ship, the Golden Hind, which landed in northern California in 1579 and described the shallow waters near Bolinas “a convenient and fit harborough.”

One can imagine the ship entering the San Francisco Bay right after that stop, marveling at the potential of a place that the Spaniards described as inhabited by so many bears that it might have been some native Eden undescribed to the outside world, setting the Bay’s mouth as a true Golden Gate before the word anchored its meaning to the very city within the world’s collective unconscious.

One finds little mention of the region’s natives until later, and perhaps some local Ohlone group told a story of a big, solitary sailing ship going north, then coming back in the other direction not long after.

After a long journey across South America, where Drake, a privateer—a “pirate,” any Spaniard would say—with permission from the British crown to raid enemy ships and cargoes, Drake proceeded to fight the strong currents of the California coast in search of a passage back to England to the north.

But he encountered freezing weather instead of the mythical Northwest Passage, turning around. Had he succeeded in finding a passage that didn’t exist, the natives of the San Francisco Bay would have faced a much earlier European push to settle in such a remote place that wasn’t connected by any land route to the rest of North America.

The San Carlos entering the Bay to meet the Ohlone

We don’t know whether Drake skipped or entered the Bay, if only briefly, on their way up to find the passage, or down after getting stuck in the freezing weather coming down from Alaska, for the first European ship to record its entry arrived to the mouth of the magnificent Bay almost 200 years later. The San Carlos anchored inside in 1775, under Lieutenant Juan Manuel de Ayala, sailing from New Spain with the clear intention of establishing the northernmost missions and presidios of the network secured by Franciscan friars along the California coast.

I’m picturing the encounter between the Ohlone on their flexible tule boats going to the encounter of the San Carlos as depicted by drawings like the one just shared by Lloyd Kahn on his feed. The oldest such drawing memorializing the use of utilitarian tule boats by the local natives is an 1822 lithograph by German-Russian painter and explorer Louis Choris, “Ohlone Indians in a Tule Boat in the San Francisco Bay”: three people paddling a reed boat across the Bay, and offering a glimpse at the life before the area’s fast transformation a mere two decades after (one year before, in 1821, New Spain had seceded from Spain, becoming Mexico).

Local Ohlone sailors might have been the first to seasonally inhabit the islands of the San Francisco Bay, which lacked any permanent, large-scale native settlement but were ideal for easy fishing, hunting, and gathering shellfish. Alcatraz, whose Spanish name describes the place’s bird population of seabirds and gannets (“alcatraces” among them), was a favorite ceremonial spot where the Ohlone might have gathered eggs.

Islands and islets inside the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area contains more than 30 significant enough islands and islets to have a distinct name. Besides the bigger Alcatraz, Angel, the artificial Treasure Island connected Yerba Buena Island, Red Rock, Brooks, and Bair Island, there are a series of islets named numerically by the US Army Corps of Engineers (Island Number 1, 2, etc.), as well as the islets and marsh islands of the Coyote Hills and Dumbarton.

To the north, where the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta meets the Bay, there are dozens more islands used for agriculture and flood control: Grizzly Island, Ryer, Sherman, Twitchell, Decker, etc.

It’s attributed to George Santayana (a Spaniard educated in the United States and hence considered Spanish-American) a very thoughtful perspective on how any societal advancement should be rooted in the long history of a place:

“Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement: and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress (1905-1906), George Santayana

That said, the very few efforts made to incorporate the Ohlone era into the history of the Bay Area risk disappearing, given the current animosity towards anything that could lead to recognition of more Native American claims. The Bay Area lacks any federally recognized tribe, and groups like descendants of the Muwekma Ohlone, the Ramaytush Ohlone, and Chochenyo Ohlone face the fact that many tribes were never formally recognized or had their status revoked a long time ago.

Convoluted origin story

Even living now in the Bay Area, I’m always amazed by the beauty of the spot Between both shores of the Golden Gate, and crossing the bridge in both directions has always made an impression on me. I haven’t visited Alcatraz and, despite driving through the Bay Bridge uncountable times, I’ve never stopped by Yerba Buena Island or the connected, bigger Treasure Island, an artificial islet built in 1936-37 for the 1039 Golden Gate International Exposition.

That said, I’ve always been fascinated by tiny islands (it is not a surprise that The Count of Monte Cristo is one of my favorite books, a very predictable thing for a boy, grown or not). When I read in the local press not long ago that Red Rock Island, a 5.8-acre uninhabited landmass in private hands near the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, was for sale again, I couldn’t help but chuckle; apparently, the island (which lacks any service and has views of the city) found an undisclosed buyer in August 2024.

Not far from Red Rock Island, just off the coast of Point San Pablo in Richmond (north of the East Bay), there’s a quaint islet with a purpose. East Brother Island hosts a Victorian-era lighthouse built in 1873, one of the oldest still operating on the West Coast. East Brother Light Station runs a bed and breakfast with views of the Bay, Mount Tamalpais, and San Rafael Bridge.

I’ve come to the Bay Area for twenty years each year and have even lived there for a while now. When I started visiting, I became interested in the early descriptions of the place, which are included in journals like those of Father Pedro Font.

I learned about the Juan Bautista de Anza overland expedition in 1975-76, the first connecting Sonora, northern Mexico (then Nueva Navarra, a part of New Spain) to Alta California (also called California Nueva or Nueva California: tanto monta, monta tanto).

Our personal encounter with Juan Bautista de Anza

Juan Bautista de Anza was a Sonoran born near Arizpe in 1736 of European descent, issued from a Basque family of long military service to the Spanish crown. Given the historical context of exploration and subjugation of Europeans towards Native Americans, records show he was honorable and had what it took to prove an overland route from the desert to California.

So, when in 2005 Kirsten and I made a trip to visit a Mexican friend of mine from Sonora with whom I had worked in Barcelona, I could imagine what could have been that first expedition. I remember how desolate the Sonoran desert feels even today. When we stopped at a place in San Carlos to stay overnight, we asked about things to do in the interior; I inquired about the Anza expedition, and somebody talked about Arizpe.

Those were pre-smartphone, pre-internet-everywhere times, so we had physical maps and our laptops with us, though we could only go online at our stops. Traveling feels already different. Anyway, the person who helped us, a middle-aged lady from the local preeminent family who owned the place at the resort in San Carlos, gave us one interesting tip: “when you arrive in Arizpe, no matter the time, just ask for El Güero and tell him you’re coming from my place.” We did so, and the person in question treated us well. I asked him (in Spanish, of course) about Juan Bautista de Anza.

“¿Anza? Sí, he’s buried here, in the church.” We entered the church and, through a glass on the floor, we saw the explorer’s resting place. The first European explorer to identify the locations of the future Bay Area settlements, the future San Francisco included. At around that time, I wrote a book (again, in Spanish) about three young Spaniards who, due to different circumstances, ended up leaving the country as castaways. They meet each other and finish their particular Odyssey in the late 18th-century Bay Area after an arduous trip helped by Franciscan friars.

Circles

I have no pictures of our trip to Sonora aboard an old, beaten-down Toyota Camry. It was the road, the open landscape, and us. We had no kids and weren’t married then. I must have lost them between hard drives and computers sometime before the invention of cloud services. I’m tasking myself with the goal of finding them at home in Spain in some forgotten hard drive. Real memories are digitally buried.

I wonder how much houses were worth in the Bay Area in the summer of 2005. It must have felt like a more innocent time, right before the place’s biggest firms became the biggest companies in the world. To this day, I haven’t met anybody claiming to be descendants of the local Ohlone tribe, though we all experience the consequences of those early European explorations across our everyday lives.

Some seem to have it easier than others based on documents that have little to do with their worth, actual origins, or allegiance to the land. Ironically, those with no claims at all in the land are part descendants of Native Americans from down south, too diluted to be considered natives of one or another kind.

As we speak, the islands and islets of the Bay Area host a bird renaissance. At least there’s that.