Collapse and anti-collapse: quiet power of self-organizing to build things

A cult sci-fi saga returns to spotlight our obsession with collapse. But not all places spiral downward. Pepe Mujica’s passing is a mirror held against the rat-race society.

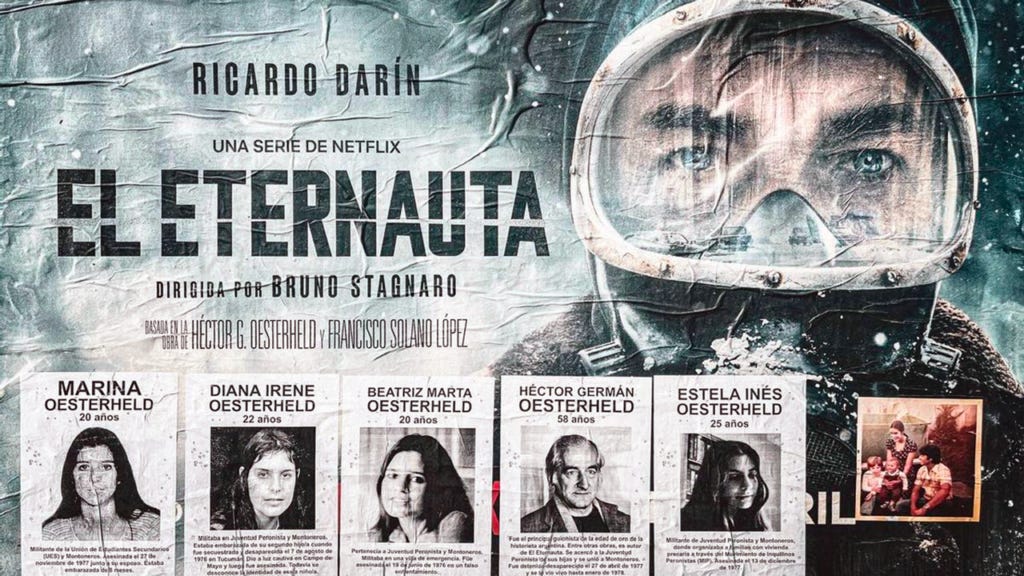

I can’t help but notice the launch of El Eternauta (The Eternaut), the TV Series adaptation starring Ricardo Darín. It is based on the legendary Argentinian comic series, which emerged in the late 1950s and kicked off the Golden Age of Argentine comics, attracting many Italian artists.

Recommendation algorithms have improved over time; it must be something related to the AI fad. Anyway, once the series was available for streaming, it began following me places, perhaps because it really takes time for me to notice new audiovisual releases: there’s only so much time, and I’d like to write a little more, to read a lot more, to spend more time in the garden (weeding, trimming, mulching, you name it), to be even more present in our everyday life. But, since it’s The Eternaut, I’ll let it pass.

All the dirty wars of all places in all of history

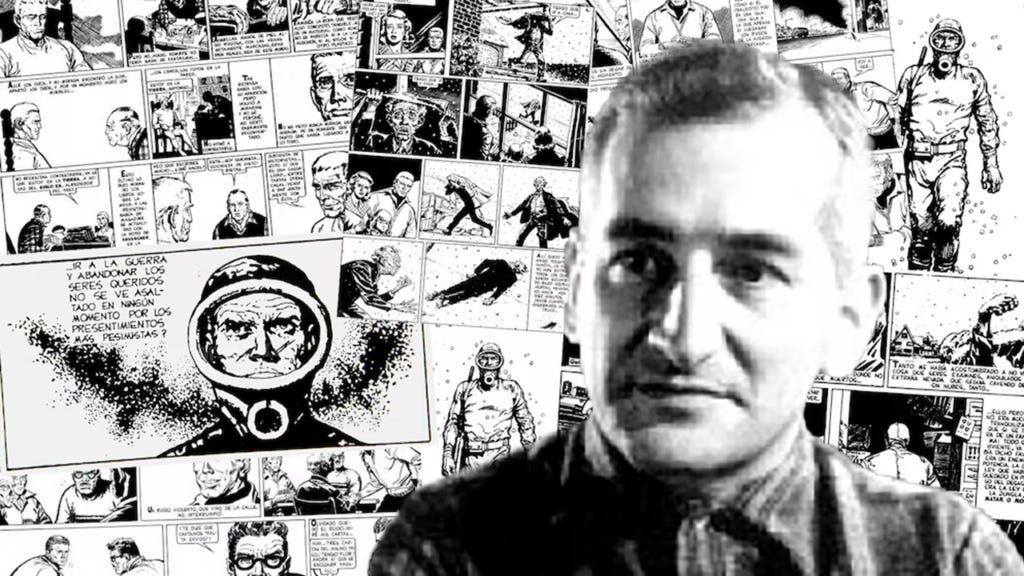

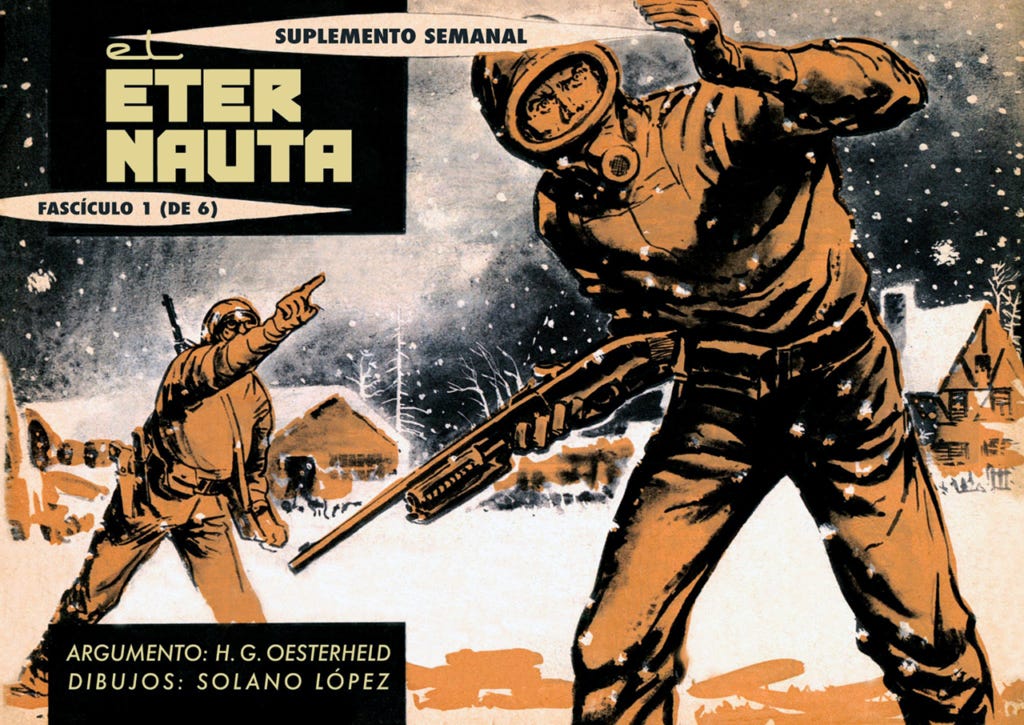

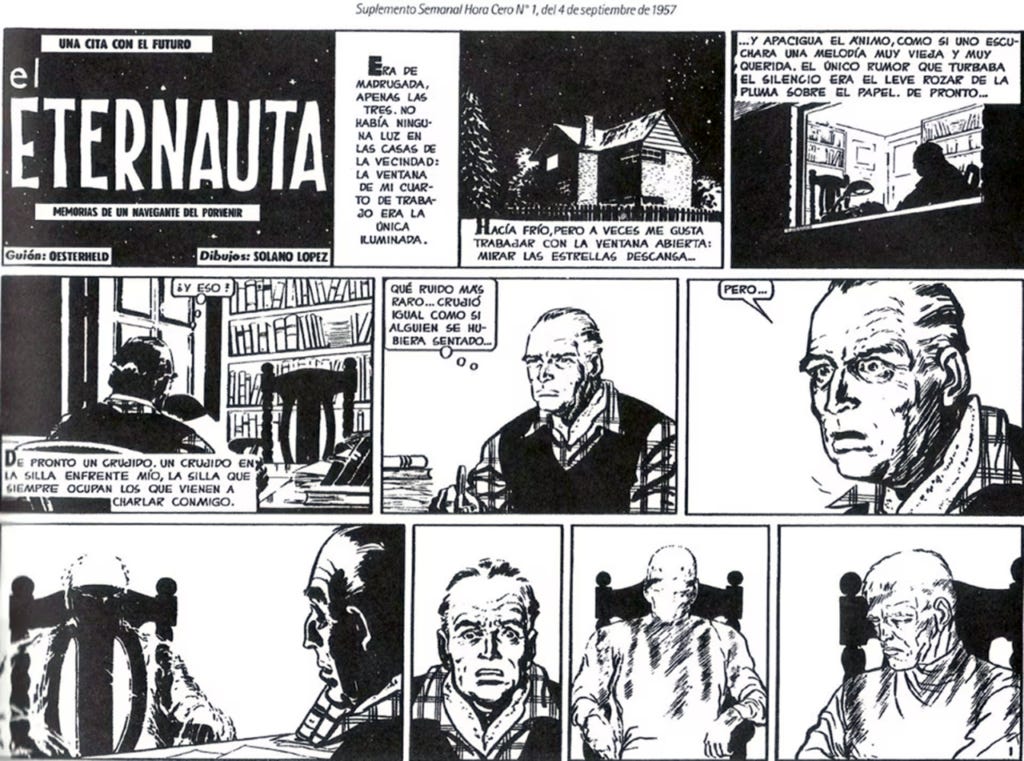

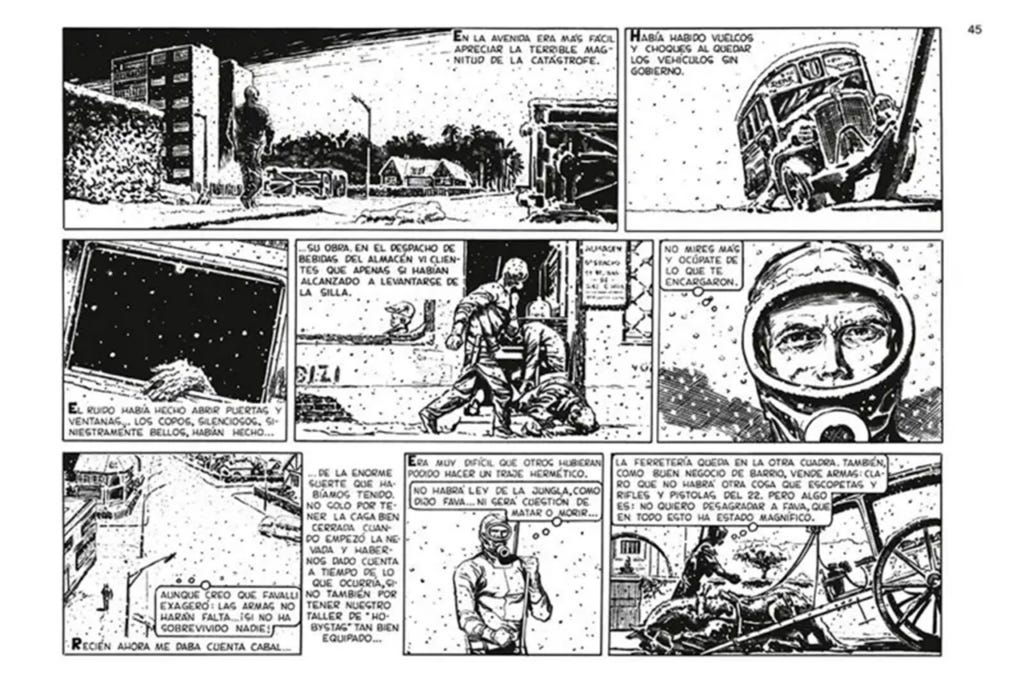

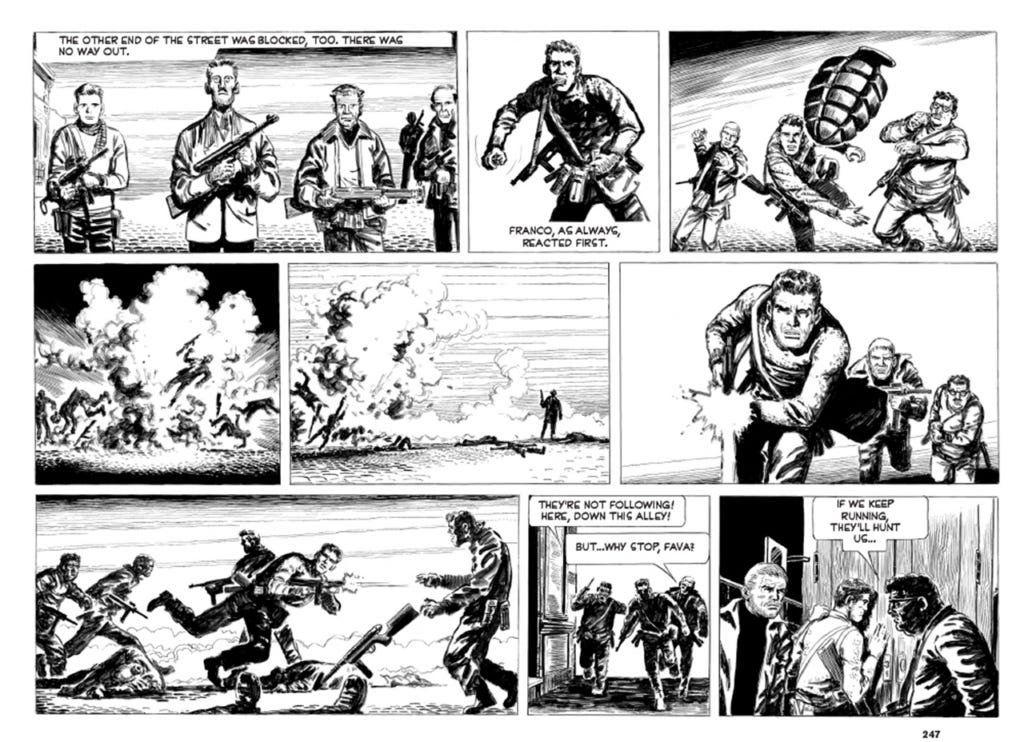

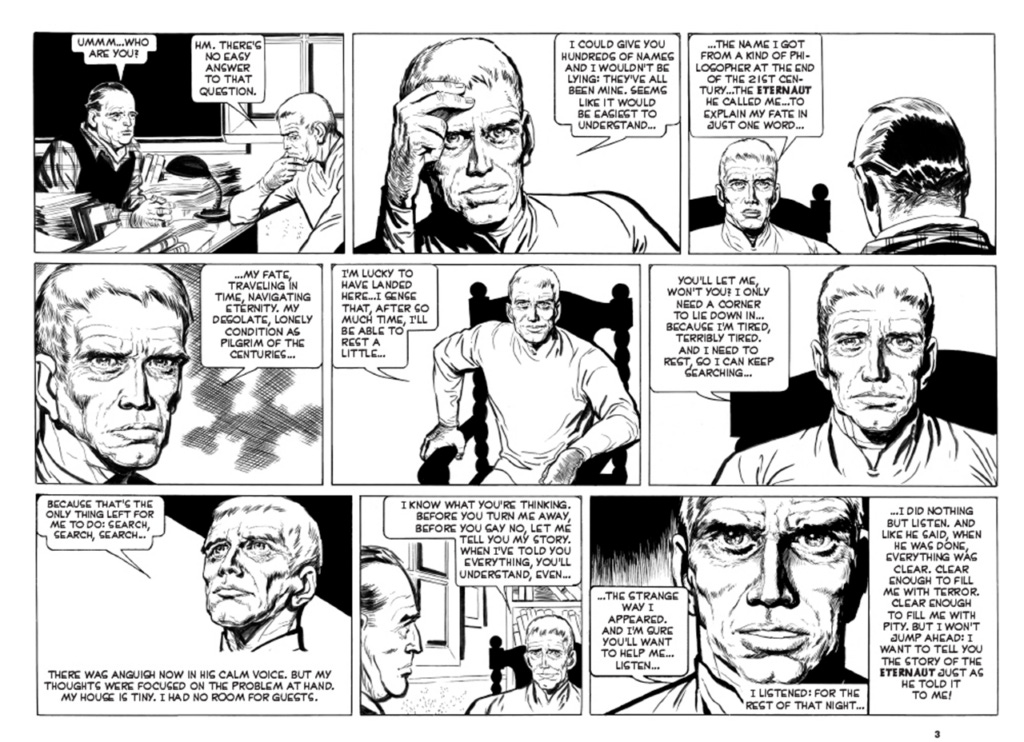

What’s The Eternaut? Since I first heard of it long ago in Barcelona, it’s remained a cult graphic novel among the Argentinian diaspora, making a dent across Europe (first published in Italy in the 60s, France in the 70s, and Spain in the early 80s). A concept by the “porteño” writer nicknamed HGO (Héctor Germán Oesterheld) and a somewhat classic artwork (think Will Eisner) by Francisco Solano López, the story is a precursor of many things, with its mature and fantastic allure of the post-apocalyptic genre that would dominate popular comics and pulp literature in the US, Japan, and Europe, for the traumas regarding World War II and the atomic threat were all too real.

I have always loved the collapsing world described by Oesterheld and put into images by Solano López because things didn’t happen in “Gotham,” Chicago, London, Paris, or Tokyo. The apocalyptic event happens in Buenos Aires, an evocative and remote megalopolis for us spectators to witness mayhem in real-time as it happens when a mysterious, deadly snowfall starts falling, and only the ones who quickly figure this out protect themselves indoors or use protective masks and gear to survive its contact. We follow one of them, Juan Salvo, the protagonist (Ricardo Darín in the series).

El Eternauta is a beautifully depicted story of collapse that doesn’t get the reader lost in the most spectacular and impersonal effects of a catastrophe that causes people to die off as they would in an all-out nuclear conflagration, a massive attack with chemical weapons, a hyper-contagious pathogen (artificially engineered or naturally occurring), or a climate catastrophe; in El Eternauta, however, the survivors learn that they face a threat of another kind, but I’ll avoid spoilers as much as possible.

Post-apocalyptic fiction and reality catching up

One thing is clear, however: we should ask ourselves why we live in a time so drawn to post-apocalyptic stories; perhaps we want to put our survival chances to the test if, for whatever reason, things were to crumble faster than expected. In many ways, the neologism collapsology (in theory, the study of the potential collapse of our modern industrial civilization) is more a state of mind than an actual discipline.

But we’ve learned something already in this century: events seem to have accelerated, and network effects don’t only refer to digital occurrences but also to the physical world, and when we switch matters in one place (say, the hardly serious game of musical chairs involving tariffs in the US) there are ripple effects across the world. It’s a three-hundred-pound gorilla of a butterfly effect.

The urban environment in which the original story of The Eternaut happens, late-fifties Buenos Aires, a city that was already called the Paris of South America for many reasons, is an ideal testing ground for showing readers what happens when electricity stops working. The societal conventions that sustain law and order in a densely populated environment suddenly collapse.

I wonder if José Saramago knew of El Eternauta before writing his Ensayo sobre la ceguera (the haunting novel Blindness). The current series adaptation retains the core narrative of a deadly snowfall and fantastic invasion in Buenos Aires, though the Netflix series updates the timeline to the present day, incorporating contemporary urban landscapes.

Both stories, The Eternaut and Blindness, are instant favorites of people who like videogames about strategy and survival, often with a post-apocalyptic allure. Unlike similar stories, these two happen in urban environments and test the biggest human experiment: the city.

When the lights go out

Which brings one big question: What happens when the lights go out, and all people are left to brace for themselves? If the technical fabric of the city doesn’t crumble semi-permanently and gets back up quickly, civility may prevail. It all becomes something people will talk about once they get over it, one anecdote that might trigger a conscientious call-to-action within high-trust, highly-prosperous societies aiming at improving their preparedness (or was it “resilience”?).

Whatever word we pick, Google Trends tells us that, worldwide over the past five years, people have favored the keyword “collapse” over any of its positive counterparts. Narrowed to the US, people are also much more interested in the term “collapse”… Que sera, sera.

Cities are complex, adaptive systems, and it’s no surprise that their proper, always imperfect, functioning relies on several interdependent layers. For contemporary cities to work, a set of things need to happen and be interiorized, perceived by those using them: relative trust and social cohesion, a sense of governance and rule of law recognized by an overwhelming majority, reliable infrastructure, a sense of inclusiveness, and the ability to “fix itself” organically by feedback and adaptation.

Many stressors make life in the city more complex. Still, some cities have been pleasant places to be (and live permanently in) for centuries, even when showing dysfunctionality and structural issues like lack of affordability, pollution, and infrastructure failures. There’s a threshold, however, that, once passed, is hard to rollback; one may call this Dantesque descent a “spiral of doom,” which happens when a vicious cycle of many factors (disinvestment in infrastructure, service cuts, insecurity and a shared sense of lawlessness) drives so many residents away that disinvestment and mistrust feed upon themselves, creating a snowball effect like the one Cleveland and Detroit experienced after the blend of suburbanization, deindustrialization and racial tensions in the late sixties.

Collective nightmare to individual hopes in Medellín

Many cities have prevented altogether, or even reversed, their spirals of doom, though it can take decades for some places to see improvements. Some of us are old enough to remember constant bad news coming out of Medellín, Colombia, once so violent and so deeply controlled by drug cartels that neglect engulfed not only the hillside slums but the whole city. Improving economic conditions in Colombia and, at the city scale, a series of local governments working across political and class divides to improve conditions made possible a turnaround from Dante’s deep rings of Inferno.

Three decades later, Medellín enjoys high levels of urban safety, relative prosperity, and well-maintained, ever-growing public infrastructure: a practical and affordable system of cable car transit (Metrocable), a network of escalators and bike paths that connect neighborhood cores with libraries, parks, and commercial areas, and high levels of civic engagement (as seen in high-trust Northern European societies). As it happens, there are realistic, incremental improvements to the lives of everyday citizens that cities, not only regions or countries, can implement and adjust to squeeze the best outcome possible for the most significant number of people. Wasn’t this the goal of good governance, no matter the ideological field that representatives at any given time owe allegiance to?

At some point in time, cities like Medellín must have felt like an actual warzone controlled by neighborhood and gang lords, much in the fashion of the lawless Mogadishu represented in Black Hawk Down (2001), or Sarajevo during the siege it experienced from 1992 to 1996 during the ethnically charged Bosnian War.

I was thinking about the landscapes of El Eternauta and the many transformations of Buenos Aires—a beautiful yet dysfunctional megacity, the capital of a no less dysfunctional country, often used as a textbook case of how advanced societies can squander their prosperity and descend into the trap of middle-income stagnation.

At some point in the Netflix adaptation of The Eternaut, the cerebral middle-aged character of Alfredo Favalli, nicknamed “Tano” (interpreted by César Troncoso), manages to catch a radio signal which allows the small group that has survived the snowfall around the story’s protagonist to briefly communicate with somebody in Montevideo on the other shore of La Plata River, which in turn tells them that the cataclysmic event seems to affect the whole hemisphere. Why does he know that? —Asks Tano. The Uruguayan explained that he’d recently talked to somebody in Southern Brazil, immediately to the north.

A quiet, healthy, relatively prosperous little country

To many, Uruguay doesn’t ring many bells, or any bell at all, especially to those uninterested in the country’s early stellar dominance of the art of playing World Cup-winning soccer, with little to envy its mighty neighbors to both the north and the south. I thought about all this as I read about the passing of José “Pepe” Mujica, who served as President of the tiny country, a place that in the early 20th century was nicknamed “the Switzerland of South America,” and not because of its landscape. It’s also been called “the quiet country” and “the country of mate and cows” (which presents serious differentiation problems with Argentina).

Ask Argentinians, and they’ll try to downplay the appellative of “the quiet country” for their small northern neighbor, stating that “quiet” and “boring” are sometimes mistaken. But we could take the urban society in the antipodes around the city of Montevideo as the anti-collapse city, the least dysfunctional among urban societies in its region.

For one, José Mujica, who refused a presidential salary or residence when he was President from 2010 to 2015, didn’t happen in a vacuum: Uruguay has cherished a long tradition of political neutrality and institutional stability, a high-trust system that pioneered a strong welfare state, universal suffrage, and democratic norms in the region.

Like Switzerland, in the mid-20th century, Uruguay had a liberal banking system with strict privacy laws that attracted foreign capital. According to some indicators, Uruguay is a high-middle-income country with quality of life, literacy, social cohesion, low crime, access to sanitation, and life expectancy indicators of a high-income country.

If we were to picture a place in the Southern Cone where a cohesive society could have a high chance of turning around any sudden collapse event, it would be the quiet urban society that, unspectacularly albeit steadily, has built a cohesive place for people to live.

Two men and a heart of gold

It’s also a place that presumed of having the world’s poorest President (materially, that is) from 2010 to 2015, whose modest lifestyle and rickety house made the veteran politician and self-described philosophical anarchist, had the nerve to pass away as the world reads about the byzantine stratagem of Donald Trump to make his country “accept” the honorability of getting a $400 million presidential plane as a “gift” from Qatar, no strings attached: George Carlin’s quick wit would have been overwhelmed nowadays.

I thought about Héctor Germán Oesterheld, the author of El Eternauta, when I read about Mujica’s death at 89 after announcing in April 2024 that he had esophageal cancer and was retiring from public view, surrounded by his family, friends, and neighbors in the rural outskirts of Montevideo.

There are striking parallelisms in the early biographies of José Mujica, the humble, tranquil philosopher-president of Uruguay in the early 2010s, and Oesterheld, the Argentine stoic, frugal author, also an anarchist in spirit. They both grew up in middle-class backgrounds and had early intellectual and political engagements.

They both radicalized in times of political upheaval in Latin America when Henry Kissinger’s mandate (as US National Security Advisor and later Secretary of State under Presidents Nixon and Ford) in the Southern Cone during the Cold War meant to offer approval and covert support for operations to destabilize democratically elected governments, support military coups, and tolerate repression in the whole region.

In the 1960s, young Mujica joined the Tupamaros, an urban guerrilla group; Oesterheld pivoted from writing traditional adventure stories to more politically engaged stories, criticizing authoritarianism through works such as El Eternauta. Both men suffered repression: Mujica spent over a decade in prison after being captured in 1970, whereas Oesterheld’s story is much sadder: after being detained by the 70s Argentine dictatorship, he was disappeared in 1977, the year I was born. Oesterheld’s four daughters (all politically active and one pregnant) also disappeared.

The anti-snake-oil seller: Pepe Mujica's unspectacular wisdom

Mujica survived prison and embraced a moderate view of progress, but never forgot the people who, like HGO in Argentina, never had a chance to go on with their lives as rightful members of their societies. Mujica embodied the possibility of redemption, while the author of El Eternauta was forcibly silenced.

That’s why his words live on in a story that continues to resonate as prophecy and warning.

I liked José Mujica’s demeanor and the way he spoke with simple words about complex matters of collective society and the individual soul. I’ve always felt like an anarchist since I was barely a teenager and began having issues with the authoritarian contradictions of Marxism and dogmatic right-wing interpretations of liberalism; discovering authors like Albert Camus in my formative years did me good, and I felt less alone right away. This is perhaps why Mujica rang a bell in me, even though I was less interested in his populist public image and more in his simple but powerful philosophical insights.

Like Juan Salvo, the protagonist of El Eternauta, Mujica knew he was no superhero (nor looked like one, that’s for sure) but an ordinary man who becomes a hero a bit in the fashion of Victor Hugo’s inspiring archetype from Les Misérables, the chameleon-like Jean Valjean: through authentic (100% NOT like Instagram or TikTok fakeness) and deep-hearted solidarity, resistance, and collective struggle.

José Mujica in real life and El Eternauta’s Juan Salvo in fiction represent the best of us in an era of over-gesticulation and micro-Napoleons with Freudian self-esteem issues, giants in a world of moral midgets, shameless spin doctors, disgusting boot-lickers, monsters of relativization, and other disgraceful creatures. Mujica and Salvo offer man’s resistance to invasion and dehumanization, a fresh anarchist view of the problem of technocratic control, and a middle finger to the Karens of the world who support it.

Triumph isn't about winning

If Oesterheld used a deadly snowfall as a metaphor for the slow, invisible forces that creep in and paralyze societies with a mix of fear, apathy, and superficial consumerism as distraction (if people can’t buy homes, let’s guarantee access to cheap, shiny goods they don’t really need), Mujica identified the creeping threats of contemporary societies that had reached his corner of the world: the culture of waste, the erosion of empathy, the death and denigration of everything deemed “slow.”

In the shadow of José Mujica’s death, the snow of El Eternauta falls heavier than ever—a quiet, deadly storm of dehumanization and indifference. Like Juan Salvo, Mujica warned us not with shouts but with the example of a life lived humbly, resisting the alien logic of greed. In a world increasingly governed by ‘Ellos,’ his absence leaves a silence that feels like exile.

Mujica would have agreed with British anarchist Colin Ward, when he argued that an anarchist society is always in existence when people organize themselves in small groups and with no need for authority:

“like a seed beneath the snow, buried under the weight of the state and its bureaucracy, capitalism and its waste, privilege and its injustices, nationalism and its suicidal loyalties, religious differences and their superstitious separatism.”

Mujica led a remarkable life despite his predilection for Seneca over the rat-race level of hiper-consumerism that isn’t making people happier but making them work harder for things they don’t need, perhaps to keep them out from asking themselves why they don’t have jobs that contribute to a productive economy nor can buy a home anymore.

“To triumph is not to ‘make it,’ it’s to get up and start again each day, to have the courage to start over—because that is what it means to live.”

A little farm outside Montevideo

Regarding his modest living means for an ex-president, he didn’t see it that way. In a 2014 interview with Spanish journalist Jordi Évole (Salvados, LaSexta TV channel, Spain), he expressed his views on this matter:

(Jordi Évole): And you’re happy here?

(José Mujica): Yes, very happy. Here I have what I need. My land to cultivate, my animals, my peace. What more could I ask for?

(Jordi Évole): There’s a clothesline with clothes hanging. (Do) You do the laundry?

(José Mujica): Of course! What’s so strange about that? We all do things here.

(Jordi Évole): It’s just… It’s striking to see a former president hanging clothes.

(José Mujica): Well, a president is just a person. A person who has a responsibility for a time. But in the end, he’s just another person. And people do laundry.

(Jordi Évole): And you have a well for water?

(José Mujica): Yes, the water here is good. We’ve always used it.

(Jordi Évole): It’s a very simple life.

(José Mujica): Simple, but with everything necessary. I don’t need more. For me, this is living. Being free to do what I like, without being a slave to material things.

(Jordi Évole): And the security? You don’t have special security here?

(José Mujica): No. The people around here are my security. And those who might want to cause trouble… well, they know they’d have to deal with me too. And I might be old, but I can still handle myself.

(Jordi Évole): (Laughs) I don’t doubt it, President.

Regarding frugality:

(Jordi Évole): President, you’ve said, “I’m not poor, frugal.” What’s the difference?

(José Mujica): Well, poverty is when you lack things. Frugality is choosing. I’m not poor, I’m frugal. I don’t need a lot. I’m happy with what I have. I don’t need to buy things to feel good. I don’t need to be showing off, or anything like that. I’m happy with what I have. And I think that’s a good way to live. Because you’re lighter, you carry less weight. You don’t have to be working like a slave to maintain a lifestyle you don’t need.

Thank you 🙂 ,

Beautiful shares about José Mujica ❤️

I knew of him and his wife ❤️ and his speech to the UN ❤️🙂

and now your story today 🙂❤️ .

It's so harsh about Argentina.

I'm lucky to be here reading your SubStack, cozy warm and safe in my home in New Mexico.

Thank you and Have a wonderful evening too 🙂❤️ !